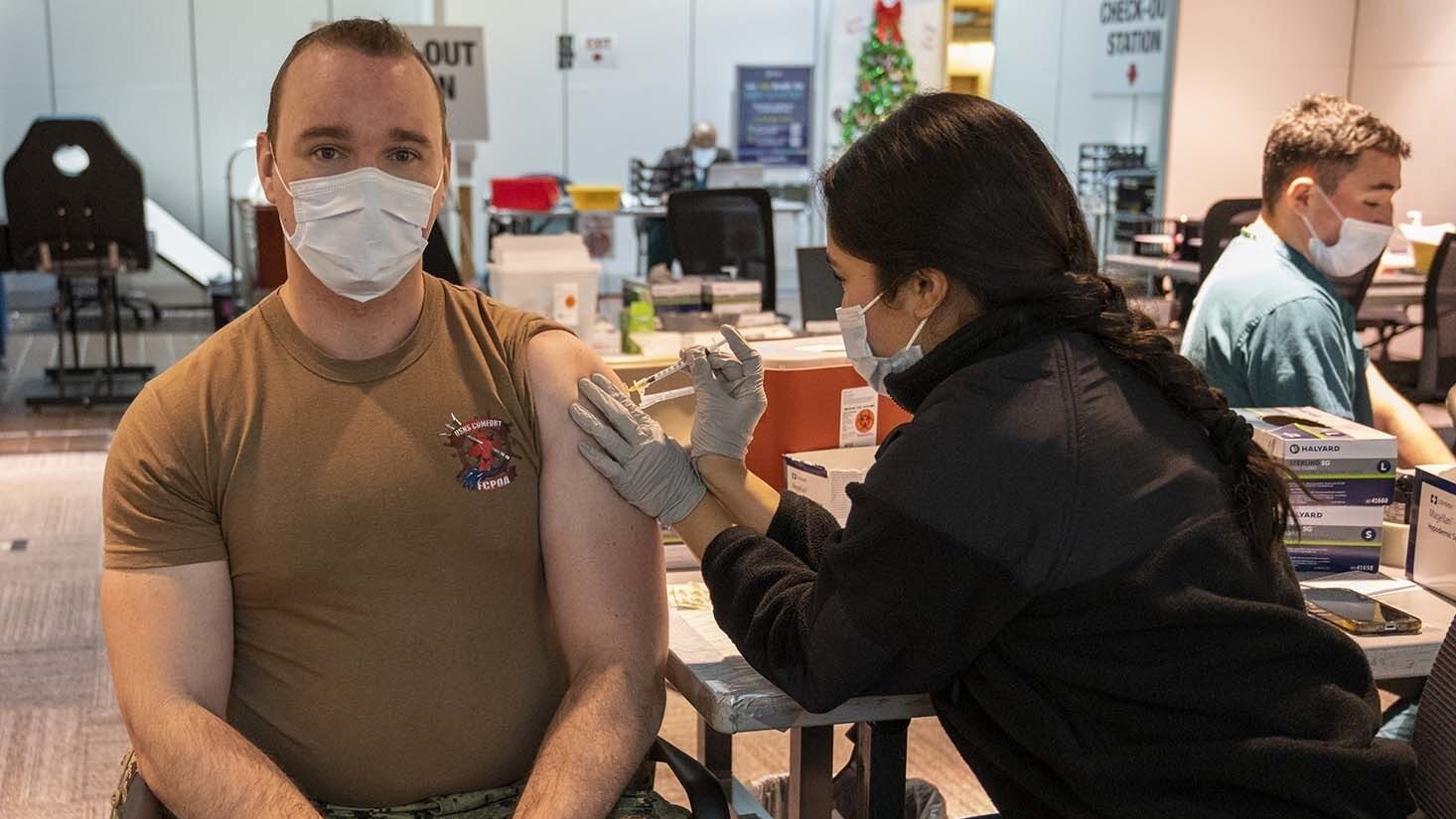

Hospitalman Apprentice Abigail Garcia administers the COVID-19 vaccination to Mass Communications Specialist 1st Jesse Sharpe at the COVID vaccination site in Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. (U.S. Navy Photo by HM3 Hunter Tactaquin.)

While the US public has largely moved past precautions for the COVID-19 coronavirus, the lessons learned since 2020 could be vital for preparing for a future global pandemic. In the op-ed below, Dan Mahaffee of the Center for the study of the Presidency & Congress makes the case that those lessons aren’t being paid enough attention to.

The world is not far removed from the COVID-19 pandemic that killed nearly seven million people worldwide and pulverized the global economy. With the pandemic less a daily threat, the focus has largely turned to questions about the source of the virus.

But while it is important to establish what went wrong on day one of the pandemic, we also need to remember what happened in the days after, and heed those hard lessons. After all, we cannot predict whether the next pandemic will begin as a lab leak, natural crossover or bioterror attack, but we can prepare our response.

The very fact that biosecurity and preparedness are not a regular part of today’s policy discussion should give us a moment of pause. Less than three years on from the COVID-19 pandemic, and just months since the World Health Organization officially declared the pandemic over, it’s clear that biosecurity is, once again, a low priority afterthought. Put simply, despite the harrowing experience of a global pandemic, we are still not ready for what will come next.

RELATED: Learning from COVID-19, Pentagon’s Biodefense Council to break down stovepipes

Recently, in a conference room in the Capitol building a group of experts convened to participate in a tabletop exercise organized by Foreign Policy magazine that posited a possible bioterrorist attack against Europe. It was striking how participants drawn from government, academia, think tanks, and the private sector felt the wargame captured the post-COVID challenges. At the same time, it remained frightening how many of the wargame’s lessons still reflected failures of past exercises and the real-world experience of the pandemic itself.

During the exercise, what started as an isolated incident rapidly spread to the global commons, and demonstrated just how vulnerable we remain. Based on a wholly viable, if alarming, scenario, participants benefited from their recent experiences with COVID. Yet it was abundantly clear that we aren’t much better prepared today than we were before the pandemic. From disjointed national, regional, and global responses, to the deeply underappreciated threat of disinformation in a crisis environment, the wargame demonstrated the significant challenges that remain in terms of biosecurity preparedness.

Fortunately, the exercise was just that — an exercise, designed to illuminate lessons that could be applied to a real-world scenario. And in that regard, several potential real-world ideas emerged. Many of these solutions are neither new nor novel, but they need repeating given how far we have yet to go in terms of preparation. Transforming preparedness from just an after-thought into a global health insurance policy will require a change in mentality for legislators responsible for health security budgets.

Developing truly global early-warning and bio-surveillance networks is essential to identifying, interdicting, and sequencing viruses before they can become global pandemics. Improving international coordination of public health information-sharing — alongside allies and NGOs — and investments in front-line health care trained to identify, isolate, and test for novel pathogens around the world can shore up the “front line” of pandemic preparedness.

This means greater coordination and cooperation between national-level and international health organizations, which requires a measure of political confidence building, particularly between China and the rest of the world — perhaps a bridge too far at the moment, but vital if the world is to be better prepared. Tools honed during the pandemic like wastewater surveillance illustrate passive mechanisms for biosurveillance. Sharing lessons learned in this emerging field will also serve to improve awareness of the emergence of novel pathogens, whilst also building that necessary coordination and cooperation.

Strengthening supply chain security, domestic stockpiles of necessary medical supplies, and international partnerships on critical logistics can offset shortfalls and disruptions during future pandemics. Funding for the strategic stockpile is key, but perhaps not as much as understanding the realistic, right mix of healthcare needs to plan for based on what we have learned from the pandemic’s lessons. It is also no longer feasible for the government to buy and own everything — a surge capacity is necessary, including the ability of the private sector to rapidly build up production capacity. At the core, we know there are certain basic medical tools we need to have on hand no matter what the next global threat looks like.

Planning for the second- and third-order effects of the worst-case scenarios will lead to better preparedness outcomes. In practice this means wargaming out novel and unexpected dependenices within the supply chain. As evidenced with Hurricane Maria in 2017, an isolated weather event in Puerto Rico had a considerable knock-on effect for global medical health care given single points of failure in the IV production chain. Such planning must consider the impact of disinformation, and the need to build mental resilience and trust among affected communities. Where threats from the natural world and bad actors, biopreparedness is not a partisan issue, but one of national resilience.

Above all else, the world must make preparedness a priority. Simply because we’ve come through the worst of the viral storm and are returning to calmer seas, doesn’t mean we can let down our guard or fail to invest in better life preservers. Biosecurity and preparedness must be a continuous priority for national governments and international health agencies. If the recent pandemic has taught us anything, it is that investing in health security must be a central feature of a global health insurance policy. Paying the required premiums today will dramatically reduce the costs when the next pandemic occurs. This is not just a matter of minimizing loss of life and economic damage, but also deterring potential bioterror attacks through resilience.

Sadly, it is not a matter of if, but when, the next global pandemic strikes. We will only have ourselves to blame if we don’t prepare today for what will almost certainly happen tomorrow.

Dan Mahaffee is the Senior Vice President, Director of Policy at the Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress (CSPC).

HASC pushes for reciprocity guidance for cloud computing in draft NDAA language

The legislation proposes that if one office in the department officially deems a “cloud-based platform, service, or application” is sufficiently cybersecure to use, then all parts of DoD can accept this ATO.